The wonders of modern technology -- Robert, Allen, Jenny, and Rob are out in the Dry Valleys, but I will keep all of you updated about their field work and experiences while sitting in Cambridge. Amazing place, wishing I was out there.... - Sujoy

12/6/2008:

We are finally in the field, hooray!

A view of the TAM taken by the helotech (she gets to sit in the

front seat so I gave her my camera to work with)

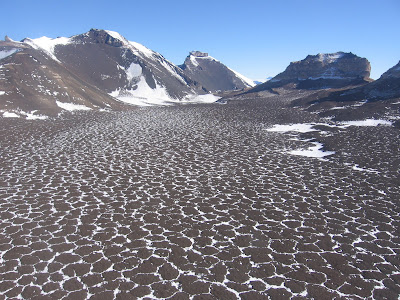

To set the scene- this place looks like a combination of Canyonlands National Park and Mars due to the combination of impressive sandstone buttes and the black/brown/red oxidized dolerites littering the ground. I would try to describe it further, but perhaps the pictures will speak for themselves.

We got here yesterday via a scenic helicopter flight across the sea ice and through the mountains. With the help of our British pilot Paul and the helotech Ally, Robert, Rob, Allen and I all crammed into the backseat of the Bell 212 for an hour long flight to our campsite. Upon arrival, we unloaded the helicopter (with rotors still spinning) and waved goodbye as Ally and Paul left us alone with 800 lbs of gear amongst the rocks and snow patches while they returned to McMurdo for the rest of our stuff. We spent the rest of the day putting up tents, carrying rock boxes from the sling load drop off to our camp, and setting up solar panels for our GPS base station, HF radio, and general electricity supply.

There are many bonuses to working in the field in Antarctica - one is the lack of ANY pests to interfere with your food or general comfort, the second is the constant availability of solar power, and the third is the ability to freeze your food simply by keeping it outside (this last one allowed us to have salmon fillets for dinner last night and steak for dinner tonight). It also means keeping water around can be a challenge.

Today we went out to explore large channels cut into the sandstone bedrock just a few hundred meters from our campsite. We also finally took our first set of samples. Perhaps the major downside to Antarctic field work is the speed at which you lose feeling from your fingers and toes whenever you stop to take a sample. In addition, our mountaineer Rob scoped out the scene for good places to make anchors so that we can take samples from the side of a cliff face in the near future. How’s that for extreme geology?

Our camp in the intermediate stage of set up

Right- this is our mountaineer Rob

12/7/2008:

With the help of a few more layers of clothing and blue skies, we headed back into the channels today to collect more samples-that’s what we’re here for after all. The sample collecting process consists of finding a good rock (ideally with large grains and easily removed from its neighbor rocks), getting the GPS coordinates, taking pictures of the area, making note of any surrounding topography that might shield the rock from the sky, using a hammer and chisel to knock the sample free, and finally stuffing it into a labeled bag. The samples are then loaded into rock boxes and transported back to the States on a big cargo ship that departs from McMurdo in February (along with all of McMurdo’s trash). Eventually (several months from now), the samples will make it back to our lab where the chemical analysis will begin.

The highlight of our work today was watching/helping Robert take samples from the side of a cliff face. Rob thought it was hilarious that Robert brought his field notebook down on the rope with him (along with his sample kit, a large stuff sack for the samples, and the camera we lowered to him on a rope when his own camera ran out of film).

Some of the sandstones here are hilariously weathered…

Allen attempts to get a precise GPS reading of his samples,

but the rocks are blocking the satellites

Robert rappels off a cliff over a perpetually frozen pond

to collect samples

12/8/2008

Today was another day of sample collecting, and something new: digging pits. The chemicals we are measuring are not only produced at the surface, but also when rocks are covered. So, in order to better understand the erosion processes going on here in Sessrumnir Valley, we dug some pits and collected the rocks we found underneath as well as collecting a whole bunch of samples in the surrounding area.

Today’s highlight was the view we got in to Wright Valley. Breathtaking. To the west is Upper Wright glacier (Manhattan could easily fit on its ice), beyond which the Polar Plateau feeds down in multiple icefalls. Directly north at the bottom of Upper Wright Valley is an area called The Labyrinth because of all the channels cut in to the rock. And to the east is a view into Lower Wright Valley and the small glaciers feeding in to it. We all decided that it was one of the most beautiful views we have ever seen.

Upper Wright Valley and the Wright Glacier as seen from the Sessrumnir Valley

We took a helicopter for our day trip to Nibelungen Valley.

We took a helicopter for our day trip to Nibelungen Valley.

Our camp in the intermediate stage of set up

Our camp in the intermediate stage of set up

Apparently, scientists on ice will do anything to fulfill the desire to engineer. Including putting themselves at risk during safety school.

Apparently, scientists on ice will do anything to fulfill the desire to engineer. Including putting themselves at risk during safety school.

Vast expanse of ice - I would say it's about yea big.

Vast expanse of ice - I would say it's about yea big.